I am a Stay-at-Home-Dad. That is what I do these days. True, I have a part-time job at a restaurant, one which allows me a much needed escape into a world of larger social interaction, of time spent with people my own age, and one which puts some cold, hard cash in my back pocket; but, by and large, I stay at home with my 11 month old son.

I stay at home with him because it makes sense on many different levels: financially, it’s much more tenable than paying for childcare in the city; economically (the economics of efficiency of movement), it’s far easier than driving somewhere to drop him off for the day, or having someone drive to our house to stay with him during the day. Not to mention that I don’t have to commute anywhere during the daylight hours in order to arrive at some work destination. Emotionally and psychologically, I find it to be far superior than allowing some third (probably non-familial, strange) party to raise my son for me. Even the best nannies have off days, the gentlest disciplinarians their downfalls: I never have to worry about that because I am the one with the occasional off-day, and I know how my son is being treated during this time period. Developmentally, also, it makes more sense for him to be connected directly with a parent-caregiver. I have, I could only imagine, so much more invested in him as a person than someone I pay by the hour to clean up after him. In the state of Georgia, babies his age who wind up in day-care centers (the least expensive option) are tended to by workers who are, as mandated by law, required to care for no more than 4 children at one time. Over the course of an 8 hour day, this means my son would receive approximately 2 hours of direct care and interaction. Over the course of an 8 hour day at home with his dad, he receives approximately 8 hours of direct care and interaction.

But I’m not here to harp on the myriad benefits of the stay-at-home life. I wanted to talk a little today about work.

Work. What is it? Who does it? Does it always result in a paycheck?

To me, work has undergone a radical shift from the time I began working to the current moment at which I find myself writing this article. The first job I ever held was at a summer camp in northeast Ohio, where my family hails from. I was 12. I recall making (what seemed at the time) the laborious, near-impossible hill climb on my mountain bike – I’m sure the tires were far underinflated, my long-range muscles years from being truly developed. Hell, it was only a distance of 2 miles, but it seemed like an ironman. I pedalled to Camp Burton, where, with the help of my dad, I had set up an “interview” with the camp’s director – a mischievous, bearded man from the mischievous, tree-bearded hills of Pennsylvania (a place I have called home on a number of occasions, a place, indeed, that happens to be where I entered the world). I don’t have the foggiest what actually went on in that “interview” any more. I do recall sweaty palms and a faltering pre-pubescent voice answering myriad questions aimed in my direction. Most of them probably had to do with “what sort of women I liked.” The camp’s director was a shameless scamp. It was shamelessly uncomfortable. Dan was always good for that: making a person feel both at home and scared shitless, all in the same moment. I got the “job.” Two hours per day, Monday through Friday, during the summer break from school. I was the “lawnmower man.” I walked behind a push mower whose self-propulsion system had seen better summers. I walked the shit out of that mower, my sneakers, and the camp’s vast acreage. I worked there, actually, many consecutive summers, increasing my responsibility and roles with each passing year. Years later, I would scratch my head in wonderment: why had I been tasked with push-mowing lawns that could easily have been mowed with the camp’s various riding mowers? (And, indeed, often were.) It wasn’t until recently, very recently, that I once again visited the subject with something approximating an iota of mental fervor. And I came to a simple and obvious conclusion: I wasn’t there to mow lawns at all; I was there to figure out how to be there. At work, that is. I was there to learn to begin the long journey of appreciating all the various forms of work available to humans – in all work’s iterations, roles, responsibilities, bosses, co-workers, etc. I learned how to make straight lines across swaths of green, true; but I came to understand a little bit about what it meant to leave the house for part of the day (and that I needed to leave by a certain time, which meant I had to be dressed and fed and rested and ready to leave at that time, which meant I couldn’t stay embedded in the couch cushions thumbing a Nintendo controller until the absolute last second – though, I know people who, after decades of doing life, have still not figured this out). It was transformational. I felt empowered. I felt important, needed. I received an actual paycheck. I paid taxes, for crying out loud. I opened a bank account and began watching numbers pile on to of each other (small ones, mind you). It felt great, and I was meeting new, interesting people all the time. Yes, including some cute girls. The gig was solid. I was 12.

It’s been almost 20 years. I’ve worked many different jobs. I’ve done a lot of different things: landscaping, disaster restoration, camp counselor, tutor, teacher, Peace Corps volunteer, international development, landscape design, kitchen worker, waiter, construction worker, farmer. Some of these have been relatively lucrative – sometimes in terms of financial remuneration (relative to effort expended), sometimes in terms of intangible reward, sometimes in terms of both (but not usually).

And now I’m a stay at home dad. And no one pays me jack.

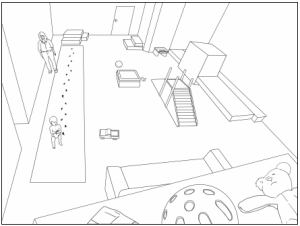

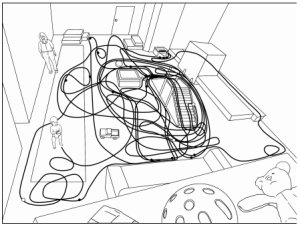

And it’s at once the easiest and hardest job I’ve ever held. The boss is unpredictable, the hours long, the work repetitive and sometimes physically demanding, the mental/emotional toll rather high at times. It’s the best and worst of life, balled up in one rather awkward cocoon. And no one pays me ni un peso to do it. And I love it (and hate it, too, sometimes).

So, in my thinking about work lately, I’ve realized something important: work looks different from different angles and to different people. It’s not a static thing. Work is not only “I leave the house at 7:45 and return to the house at 6:15.” Though, of course, for many people it is just that. Work can be not leaving the house, hell these days, not leaving the couch. And it can be watching your child, and writing novels, and painting pictures of people seen at great distances from rooftops.

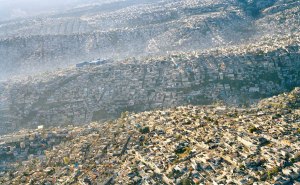

And so, when someone says something like “shoot, staying at home sure sounds like a breeze” or “man, you really need to work more and stop being such a bum” it makes me want to punch them in the face. But, then I step back and (once my heels have cooled a bit) take the zen view of things: this person has probably never had a chance to really understand the essence of work. This person has, likely, only one narrow conception of this thing that is work. And it looks something like: leave the house in the morning, slave away doing something you probably don’t enjoy for someone you probably don’t like or respect, return home in the evening, wait for the bi-weekly paycheck, repeat. Just to be clear: there is nothing wrong with this. I have done this, and I’m sure I’ll do it again. But it’s not the only way to do work, or life. The sooner we start understanding this as a society at large, the better.

Kahlil Gibran says this of work:

“You work that you may keep pace with the earth and the soul of the earth. For to be idle is to become a stranger unto the seasons, and to step out of life’s procession, that marches in majesty and proud submission towards the infinite.

Work is love made visible.

And if you cannot work with love but only with distaste, it is better that you should leave your work and sit at the gate of the temple and take alms of those who work with joy.

For if you bake bread with indifference, you bake a bitter bread that feeds but half man’s hunger. And if you grudge the crushing of the grapes, your grudge distills a poison in the wine. And if you sing though as angels, and love not the singing, you muffle man’s ears to the voices of the day and the voices of the night.

And in keeping yourself with labour you are in truth loving life, And to love life through labour is to be intimate with life’s inmost secret.”

Here’s to a world ever-advancing toward a vision of work (labor) that cannot be boxed by corporations.